|

Punch; or, The London Charivari, 1841–1992, 1996–2002 | |

Sequence |

Volumes 1–63, 1841–1872 |

Editor |

Joseph Stirling Coyne, Mark Lemon, and Henry Mayhew, 1841 |

Publisher |

R. Bryant, 1841 |

Printer |

Joseph Last, 1841 |

Price |

3d.(1841–1844); 4d (1846); 3d.(1847–1900+) |

Format |

Demy. 4vo. |

Pages |

12 (volume 1), 10 (volume 2–179+) |

Frequency |

Weekly |

Circulation |

5–6,000 (1841), 23,000 (1844), 33,000 (1850), 60,000 (c. 1860) |

Indexes |

All volumes; list of large and small engravings; six-monthly volumes include a list of selected articles. |

Copies |

Leeds University Library |

Introduction | |

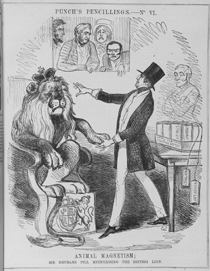

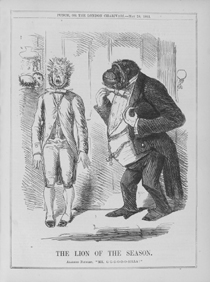

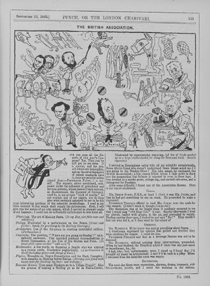

Undoubtedly the most famous comic periodical in Victorian Britain, Punch first appeared on British newsstands on 17 July 1841. It originated in the attempt by the engraver Ebenezer Landells, the printer Joseph William Last and the journalist Henry Mayhew to make a living from a new cheap illustrated comic periodical. This was a risky move in a period when the genre of comic journalism was troubled. The rapidity with which comic journals rose and fell testified to the fact that by the late 1830s the indecent, slanderous and subversive satire that had proved so popular during the politically turbulent early decades of nineteenth century Britain was failing to amuse the emerging refined and 'middle class' tastes of the chief consumers of comic literature. A more respectable form of comic journalism was needed to cater to this expanding and economically powerful readership. Landells, Last and Mayhew were part of a much wider circle of struggling writers and artists who earned their crust from stage farces, political satires, comic weekly newspapers, illustrated books and other staple features of the early Victorian middle-class diet of literature and amusement. Their circle included Gilbert Abbott à Beckett, Stirling Coyne, Douglas Jerrold, Mark Lemon and others who accepted Mayhew's invitation to contribute to the new journal. After a string of meetings, the initial articles of agreement were drawn up with Landells and Last as engraver and printer respectively, and ownership of the periodical held by Landells and Last, with a third share divided between the three editors Coyne, Lemon and Mayhew. Punch was not an instant success. Despite forceful advertising and favourable reviews in some quarters of the press, initial sales hovered around only 5-6,000 copies and this lost money for the proprietors (Fox 1988, p. 217). Punch's shaky start prompted Last and Landells to sell their shares in the business and move on to other periodical enterprises. Punch's founders tried various strategies of saving the periodical. For the first number of 1842, for example, they substituted a comic 'Almanack' which reputedly boasted a circulation of an astonishing 90,000 and which remained the first issue of the year until 1846 when it was released as a separate publication (Spielmann 1895, p. 33). More important to Punch's commercial stability was the intervention of the wealthy publishing firm of Bradbury & Evans who took over the printing of the journal in mid-1842 and by December of that year had bought the shares of all the original proprietors.  The steadying effect of Bradbury and Evans's takeover gave the periodical's first editors and contributors the freedom to experiment with format. The outcome of these experiments made Punch the success that it became by the late 1840s. Punch succeeded by reinventing the genre of comic journalism. Drawing on the better aspects of existing comic periodicals—from the cheapness of such scurrilous weeklies as the Satirist to the refined textual and graphical humour of more expensive journals such as Thomas Hood's Comic Annual—Punch offered an altogether more refined brand of humour than any previous cheap comic weekly. Although the early volumes of Punch contained much crude caricature and political invective that made it indistinguishable from such predecessors as Figaro in London (on which à Beckett and Jerrold had worked) and which provoked waspish responses from its targets, by the late 1840s Punch had settled down into a more uniformly respectable institution of cultural life. It was this formula that by the early 1860s was securing Punch sales figures in excess of 60,000, which put it far ahead of Fun (1861–1901) and other leading rival comic serials (Ellegård 1990, p. 374). Punch's formula succeeded for several reasons. Its 10–12 double-columned pages offered more variety and quality than its predecessors: it contained a generous helping of illustrations (notably the regular full-page political cartoon), genres and font styles, and it boasted the considerable skills of such writers as Jerrold, William Makepeace Thackeray and Francis Cowley Burnand, and the fine draughtsmanship of Richard Doyle, John Leech, and John Tenniel. It was the weekly informal meetings of these, mostly male, contributors at Punch's famous deal table and their submission to the gentle cajoling of Mark Lemon and later editors that played a crucial role in giving Punch a coherent voice. Another crucial ingredient was the creation of a fictional editor, 'Mr. Punch'. Fictional editors had been exploited in Fraser's Magazine and other earlier journals with humorous material, but few succeeded like this adaptation of a well-known and cherished fairground character in becoming an institution of British cultural life. He gave Punch a heart and a mind through his 'signed' articles and by implicitly sanctioning the efforts of his contributors which, with the exception of illustrations, were usually anonymous. He set the moral tone through incisive and sober outbursts against corruption, fraudulence, greed, and injustice, but made his comedy more accessible by focussing it more on the domestic world that was the hub of middle-class life. Although regular features such as the week's large political cut and 'Punch's Essence of Parliament' gave Punch a distinct political tone, the remainder of the periodical was at least as preoccupied with children, holidays, manners, pageants, language, and servants as the United States of America, public health, quackery, statesmen, the Irish, and Roman Catholicism. Indeed, as Altick suggests, Punch made its political commentary more incisive by relating it to domestic and familiar material: squabbling statesmen were represented as fighting schoolboys and troublesome parliamentary legislation was treated like a delicate newborn baby (Altick 1997, pp. 127–133).  Whether the subject was political or domestic, Punch constantly aimed to be topical and comprehensible to its readers, with whom Punch contributors shared middle-class values and familiarity with the 'World City' named in the journal's subtitle. Shirley Brooks, Punch's editor during the 1870s, neatly captured his colleagues' objectives when he reminisced that Punch 'set its watch by the clock of the [London] Times' (Briggs and Briggs 1972, p. xviii). Looking over thirty years of the periodical shows how closely it tracked the events and personalities that, however briefly, were the stuff of newspaper stories and society gossip. Reducing statesmen to schoolboys was, of course, one of a plethora of ways in which Punch gave readers a distorted, but no less instructive, view of this material. Jaunty and serious commentaries on news items, visual and textual puns, parodies of well-known dramas and songs, spoof reports, letters from fictional characters, and single line jokes enabled Punch to convey, with a directness and richness absent in other publications, the vices and virtues of life in Victorian Britain. The physical form of Punch changed steadily over its nineteenth-century life. The quality of paper steadily improved with the reduction in costs of paper and improvements in printing techniques. By the mid-1890s the periodical looked different from its early Victorian ancestor, with smoother, higher quality paper allowing lighter print, and illustrations boasting a much greater range of greys and in some cases, colour. Although the style of the periodical underwent subtle changes over its nineteenth-century period, many of the mechanisms that it used to comment on science hardly changed at all. It revelled as much in comic scientific forecasts at the end of the century as it had done in its early decades. Its 1857 hopes for cooking by electricity (volume 33 (1857), 198) were almost as prophetic as its 1881 anticipation of a 'Photophone' (Punch's Almanack for 1881, p. 11). Punch long remained preoccupied with the contrasts between the progressive realm of scientific, technological and medical development and the more conservative and convention-bound domain of the domestic and social. What happened when these domains touched was as intriguing for Mr. Punch at the beginning as at the end of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1845 it suggested that the electric telegraph could improve communication between a husband and wife who were not on 'speaking terms' (volume 9 (1845), 21) and over forty years later it showed the ghostly image of a housekeeper spying through the keyhole of a door, the 'interesting result attained, with aid of Röntgen rays, by a first-floor lodger when photographing his sitting-room door' (volume 110 (1896), 117). One of the most striking changes in Punch was the increase in the number of individuals who were chosen for the subject of illustrations. By the 1870s these were more realistic and less caricatured than the cartoons that Doyle and Leech drew for Punch in the early 1840s, but were aimed at individuals from a far broader section of cultural life, including the sciences. Portraits displayed in other periodicals, books, photographic shops, art galleries, and elsewhere deepened reading audiences' familiarity with scientists as much as other cultural figures and this made it easier for Punch to turn to such individuals as the basis for its cartoons. Accordingly, Punch participated in the personality cult of the scientist which, as Browne has suggested, was one of reasons why we should not underestimate the role of comic periodicals as 'shapers–maybe even realizers–of nineteenth-century popular thought' (Browne 2001, p. 509). | |

Notes on Indexing | |

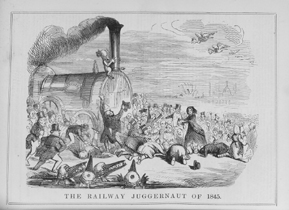

The following index covers Punch's first thirty years, corresponding roughly to the editorship of Mark Lemon. The volumes covered by the period 1841–1872 embrace some of the most significant developments in nineteenth-century science, technology and medicine, including Darwinian evolution, the electric telegraph, and the first public health acts. Scientific, technological and medical events were key sources of the visual and textual variety that helped create and sustain Punch's large readership. In 1860 Punch called itself 'the first scientific journal of the day' and while this was not meant to be taken seriously, it represented scientific endeavour to its readers with the same sharpness that underpinned its comic reproductions of other material. The implications of railway 'progress', Darwinian evolution, and women doctors were hardly expressed more succinctly than in a map of England completely covered with railroads (volume 9 (1845), 163), Leech's cartoon of an ape carrying a placard with the words 'Am I a man and a brother?' (volume 40 (1861), 206), and George Du Maurier's cartoon of a man feigning illness so he can be treated by a 'rising practitioner', a lady physician (volume 49 (1865), 248). Scientific material was exploited for many reasons. When science was the subject of extensive debate elsewhere, when it was on public show, and when it appeared to be bogus, heroic, dangerous or ingenious, then Punch usually responded in a variety of ways. It was outraged by news of medical malpractice and threats to public health, it revelled in the pageantry of the Great Exhibition and the British Association, it eulogised Florence Nightingale's work in Sebastopol and Michael Faraday's analysis of filthy 'Father Thames', it poked fun at abstruse scientific words and ridiculed the mania for new railway schemes, and expressed its admiration for the telegraph by proposing its own far-fetched extensions of the new communication technology. Scientific material was most likely to appear in commentaries on news reported elsewhere, but equally significant material was introduced across the genres that constituted Punch from puns to large engravings.  Punch's 'scientific' articles typically contained a good deal of non-scientific material. Indeed, it was precisely by associating science, however incongruously, with the domestic, political, and social that Punch could bring out the wonderful, comic and worrying implications of scientific endeavour. Punch's 'scientific' material accordingly participated in the broader tonal changes taking place in the journal throughout the nineteenth century. While early caricatures of medical 'types' and spoof proceedings of scientific societies hark back to the style of such waspish scientific satirists as William Hone and the writers of Martin Scriblerius(1714), by the 1850s Punch's scientific material was more respectable and for some commentators, less funny. A good example of this shift is furnished by George Du Maurier's 1865 cartoon of a woman doctor (volume 49 (1865), 248) which is a good deal more realistic and less caricatured than Leech's 1842 cartoon of a medical student (volume 2 (1842), 71). As we have seen, such changes were the result of Punch catering to the new tastes of middle-class readers, but also because Punch was increasingly dominated by writers and artists such as Brooks and Tenniel who learned their trades in the more genteel world of early Victorian publishing. Always keen to capitalise on the success of their periodical, Bradbury & Evans repackaged Punch into six-, twelve-, eighteen- and twenty-four month bound volumes of the periodical. Each one was bereft of the original advertising material that adorned each issue, but now included a title page, a short preface, and an introduction listing significant articles in the volume and, usefully for the historian, explaining some of the obscure events that were the talk of London town for a brief period. Volumes representing the January–June period also came with the considerable bonus of the rich Punch's Almanack which constituted the first issue of Punch each year until 1846, when it was issued in December as a separate publication. Most publicly available runs of Punch comprise bound volumes and it is these repackaged forms, including title page, preface, introduction, and Almanack that have been indexed here.  One of the obvious features of Punch is that, with the notable exception of most illustrations, the articles are unsigned. The identity of the artists has been deciphered using the handy table of artists' signatures published in Spielmann 1895, pp. 573–74). The identity of writers is much more problematic. In some cases, this is easy to establish because the articles were republished in book form with the author's name restored, or because some accounts of the periodical and its contributors have been generous enough to reveal this information (for instance, Jerrold 1910). Drawing on published sources, this index has identified writers and artists who contributed anonymous or pseudonymous material. Unpublished sources, however, provide the most important tool for establishing who contributed what to Punch. The Punch archives in Knightsbridge, London, currently owned by the Harrods proprietor Mohammed Al-Fayed, contain ledger books listing the names of writers and artists against titles of texts or illustrations and the amount of column space (and therefore payment) represented by the article. The ledgers start with the issue for 4 March 1843 and continue uninterrupted, with several short gaps, until the twentieth century. Owing to constraints of time, however, it has not been possible to include this information, but it is hoped that scholars wishing to identify contributors will make use of the Punch archive. Given the comic style and ostensibly domestic and political content of Punch, it has been especially fruitful to undertake an inclusive reading of all the periodical. Texts and illustrations whose titles and captions suggest little scientific content frequently turned out to contain important material on that subject. Conversely, a small proportion of articles whose titles included scientific, medical or technological terms had little to do with those subjects. A good example is railways. Many articles on this subject were not indexed because the articles were wholly concerned with financial corruption in the railway business. It has been the policy throughout this index to try to include articles that, irrespective of size, contain references to science, technology and medicine that were important at the time and are of significance to scholars today. Thus a short pun on the word spectrum analysis (volume 57 (1869), p. 65) is included as well as a full-page cartoon of the Atlantic telegraph (volume 35 (1858), p. 77) since both help us develop our picture of the embeddedness of science in general culture. So much of Punch works by allusion. The detection and deciphering of allusion requires close reading of texts and illustrations and a considerable knowledge of the historical context. Many Punch allusions are so obscure that even the most knowledgeable Victorianists have thrown up their hands at the prospect of understanding them. Fortunately, however, most of the allusions in Punch's scientific material are relatively easy to decode and where necessary this index provides the reader with brief explanations of the events, people, places, publications and institutions sometimes only darkly hinted at. | |

Bibliography | |

Adrian, Arthur A. 1966. Mark Lemon: First Editor of Punch Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966 Altick, Richard D. 1991. 'Punch's First Ten Years: The Ingredients of Success', Journal of Newspaper and Periodical History, 7, 5–16 Altick, Richard D. 1997. Punch: The Lively Youth of a British Institution 1841–1851, Columbus: Ohio State University Press Briggs, Asa, and Briggs, Susan, eds. 1972. Cap and Bell: Punch's Chronicle of English History in the Making, 1841–61, London: Macdonald Browne, Janet 2001. 'Darwin in Caricature: A Study in the Popularisation and Dissemination of Evolution', Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 145, 496–509 Doran, Amanda-Jean 1991. 'The Development of the Full-Page Wood-Engraving in Punch', Journal of Newspaper and Periodical History, 7, 48–63 Fox, Celina 1988. Graphic Journalism During the 1830s and 1840s, New York: Greenwood Press Graves, Charles L. 1921–22. Mr. Punch's History of Modern England, 4 vols, London: Cassell and Company Ltd. Jones, John Bush and Shaw,Priscilla 'Artists and "Suggestors": The Punch Cartoons 1843–1848', Victorian Periodicals Review, 2, 2-14 Layard, George Soames 1907. A Great "Punch" Editor: Being the Life, Letters and Diaries of Shirley Brooks, London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Leary, Patrick 2002. 'Table Talk and Print Culture in Mid-Victorian Britain: The Punch Circle 1858–1874', unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Indiana Noakes, Richard 2004a. 'Punch and Comic Journalism in Mid-Victorian Punch', in Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical: Reading the Magazine of Nature, ed. by Geoffrey Cantor et al., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 91–122 Noakes, Richard 2004b. 'Representing a 'Century of Inventions': Nineteenth-Century Technology and Victorian Punch' in Culture and Science in the Nineteenth-Century Media, ed. by Louise Henson et al., Aldershot: Ashgate, 151–163 Paradis, James G. 1997. 'Science and Satire in Victorian Culture', in Victorian Science in Context, ed. by Bernard Lightman, Chicago: Chicago University Press), 143–157 Price, R. G. G. 1957. A History of Punch, London: Collins Spielmann, M. H. 1895. The History of "Punch", London: Cassell | |

Richard Noakes | |