|

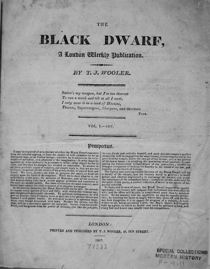

The Black Dwarf, 1817–24 | |

Sequence |

Volume 1, 1817 |

Editor |

Thomas J Wooler, 1817–24 |

Publisher |

Benjamin Steill, January–April 1817, |

Printer |

Benjamin Steill, January–April 1817, |

Price |

4d. (February–June? 1817), 2d. (June? 1817–19), 6d. (1819–) |

Format |

Demy 4to. |

Pages |

8 [=16 columns] (1817) |

Frequency |

Weekly |

Circulation |

12,000 (1819) |

Indexes |

All volumes |

Copies |

Leeds University Library |

Introduction | |

Thomas Wooler (1786?–1853) began his radical weekly, The Black Dwarf, on 29 January 1817, just two months after William Cobbett began to issue the enormously successful two-penny edition of his Weekly Political Register—his 'two-penny trash', which so terrified Lord Liverpool's repressive administration. Though initally priced at fourpence, the Black Dwarf rapidly rose to prominence as a leading journal among the radical working classes. In the summer of 1817, Wooler's arrest and trial for seditious libel (from which charge he successfully defended himself), combined with Cobbett's flight to America and a reduction in price to twopence, led to the Black Dwarf becoming probably the most prominent of the radical journals of the late 1810s. By October, the Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, complained before Parliament that it was to be found everywhere, including, in one northern mining area, 'in the hatcrown of almost every pitman you meet'. Wooler had taken Cobbett's place as 'the fugleman of the Radicals' (quoted in Wickwar 1928, p. 57). The Black Dwarf was a key source of political information for radical workers, who reportedly clubbed together to purchase and read the journal, so that the reported circulation of 12,000 in 1819 undoubtedly translates into a significantly higher readership (Webb 1955, p. 50). It was also a means of organizing political action, and Ian Haywood claims that it 'played a key role in creating the climactic event of 1819, the mass meeting in Manchester which became immortalised as "Peterloo"' (Haywood 2004, p. 94). Ironically, it was that event which ultimately led to the Black Dwarf's decline, since the repressive 4½d. newspaper tax imposed in the aftermath in order to suppress the radical press resulted in its increased price of a prohibitive sixpence. While the Black Dwarf continued into the 1820s, its impact, like that of other leading radical journals of the post-war period, was clearly dented. Wooler had been apprenticed as a printer before moving to London from Yorkshire and becoming involved in metropolitan radicalism. He had some experience of radical journalism before beginning the Black Dwarf, and had also published a journal of theatrical criticism, The Stage (1814–16). His love of the stage was evident in the Black Dwarf, in which occasional theatrical reviews appeared. The new journal, however, was dominated by political commentary and analysis, usually with a statirical hue. Its title apparently alluded to the north-country belief in a malign magical fairy, responsible for all kinds of mischief—a notion that had been given contemporary form in Walter Scott's tale, 'The Black Dwarf', which appeared in his Tales of My Landlord in 1816. Wooler applied to himself the fictional persona of the 'Black Dwarf', and a 'Prospectus' published on the title-page to the first volume speculated about whether he was demonic or divine before assuring readers that he would 'expose every species of vice and folly'. Wooler also included in his journal a regular series of editorials entitled 'Letters of the Black Dwarf', which were addressed 'to the Yellow Bonze at Japan', and in which he commented on contemporary events. Much of the rest of the journal was clearly also written by him, but there were also apparently contributions from others, albeit that some of these may have come from Wooler's own hand. In fact, Wooler was known to compose the text of his articles as he composed the type, a point which he used in his defence at the 1817 trial—he had not 'written' his articles at all (Hendrix 1976, p. 110). The liveliness of Wooler's satirical prose was a key element in the journal's success, as also was his continuing involvement as a political orator. He spoke in favour of the parliamentary petitions of his friend Major John Cartwright, and spent a period in prison in 1820–21 following a political meeting in Birmingham, when Cartwright provided the money necessary to maintain the Black Dwarf. In the rapidly moving world of radical politics, however, the Black Dwarf's star soon faded, to be replaced by new journals in the 'war of the unstamped' of the early 1830s. | |

Notes on Indexing | |

As a purely political paper, the Black Dwarf contained no scientific articles as such. The one scientific subject properly belonging to the Black Dwarf was political economy, and there is some discussion of this topic, with critical commentary on both Thomas Malthus's bleak analysis of the principles of population and Robert Owen's visionary communitarian schemes. Nevertheless, as Hendrix points out, Wooler's primary focus was on 'politics rather than economics' (Hendrix 1976, p. 109). In addition, though, the highly colourful prose style of radical journalism at this period, and of Wooler in particular, was heavily laced with scientific, medical, and technical imagery. Medical imagery was particularly common, with references to the ills (and plagues) of the state, to political leeches, and to other cruel treatments handed out by 'state physicians', but Wooler could also describe politicians in natural historical or astronomical terms. Also interesting is Wooler's repeated use of a discourse of natural law, which was common to much radical journalism. The laws of nature and the natural state of the world, often underpinned by divine dictates, were used to enforce the radical political analysis and to argue for the unnaturalness of the prevailing state of affairs. The indexing provided here extends only to the first volume, but is sufficient to provide a sense of the standard forms of scientific reference in Wooler's political vocabulary. In order to make the passing references to scientific subjects accessible and intelligible, the indexing has generally involved providing relatively detailed descriptions, designed to explain the relevant quotations within the original context. | |

Bibliography | |

Altick, Richard D. 1998. The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900, 2nd ed., Columbus: Ohio State University Press. Epstein, James 2004. 'Wooler, Thomas Jonathan (1786?–1853)', in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography:from the Earliest Times to the Year 2000 , 60 vols, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 60: 251. Gilmartin, Kevin 1996. Print Politics: The Press and Radical Opposition in Early Nineteenth-Century England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Heywood, Ian 2004. The Revolution in Popular Literature: Print, Politics, and the People, 1790–1860, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hendrix, Richard 1976. 'Popular Humor and "The Black Dwarf"', Journal of British Studies, 16, 108–28. Klancher, Jon P. 1987. The Making of English Reading Audiences, 1790–1832, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. Webb, R. K. 1955. The British Working Class Reader, 1790–1848: Literacy and Social Tension, London: George Allen & Unwin. Wickwar, Wiliam H. 1928. The Struggle for the Freedom of the Press, 1819–1832, London: George Allen & Unwin. | |

Jonathan R. Topham (nos. 1–31) and, Fern Elsdon-Baker (nos. 32–49) | |

© Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical Project, Universities of Leeds and Sheffield, 2005 - 2020

Printed from Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical: An Electronic Index, v. 4.0, The Digital Humanities Institute <http://www.sciper.org> [accessed ]