|

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, 1817–1980 | |

Sequence |

Volumes 1–2, 1817–18 |

Editor |

James Pringle and Thomas Cleghorn, April–September

1817 |

Publisher |

William Blackwood / Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy (London),

April–September 1817 |

Printer |

Oliver & Boyd, 1817–18+ |

Price |

2s. 6d. |

Format |

Demy 8vo. in 4s |

Pages |

108–34 (1817–18) |

Frequency |

Monthly |

Circulation |

3700 (1817) |

Indexes |

All volumes. Vol. 2: Index to Promotions, Births, Marriages, and Deaths |

Copies |

Leeds University Library |

Introduction | |

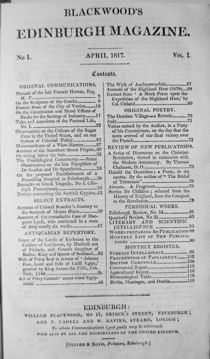

Magazines with histories as long and proud as that of Blackwood's Magazine tend to obscure the uncertainties of their beginnings. Unquestionably the magazine which the Edinburgh publisher William Blackwood (1776–1834) began in 1817 was not much like the magazine later famous for the 'Noctes Ambrosianæ' or for the serialized fiction of John Galt, George Eliot, or Anthony Trollope. It did not even have the same name, being the Edinburgh Monthly Magazine until its relaunch in October 1817, when Blackwood took over the editorship after the end of the first volume. Moreover, the magazine continued to change and evolve rapidly over the first few years. Not surprisingly, the innovations with which the magazine is associated—the shift from the miscellaneous repository of universal knowledge to the racy and often humorous literary magazine containing a range of articles, sketches, and fiction—were not developed overnight. Blackwood's motives for founding the magazine were multiple. As a forty-year old publisher who was beginning to make a significant reputation for himself, it allowed him to stake his claim in Edinburgh's literary marketplace against the growing might of Archibald Constable, the editor of the Edinburgh Review. With a growing literary coterie centred on his new premises in the recently built Princes Street, a magazine was an excellent way to capitalize on and foster their talent. In addition, William Blackwood's ambition was to produce a more lively Tory counterblast to the Whig politics of the dynamic Edinburgh Review than was provided by the London-based Quarterly. The new magazine was intended to provide scope for the young Tory wits of Blackwood's circle; to exhibit humour and vivacity in its monthly reply to Constable's quarterly. The utter misfiring of the first version of the magazine is to be attributed to Blackwood's choice of editors. James Pringle and Thomas Cleghorn organized the Edinburgh Monthly Magazine as a traditional miscellany, subdivided into sections, and they pursued their plan in a generally staid and less than competent manner. Blackwood complained that they failed to obtain sufficient contributors, and they failed even to deliver the hoped-for counterblast to Whig principles. Within three months Blackwood had stepped in to inform them of his dissatisfaction, and at the end of six months they departed acrimoniously, taking over the editorial chair of Constable's Scot's Magazine (1739–1817) under the new title of the Edinburgh Magazine, and Literary Miscellany (1817–26). Blackwood now took the magazine under his own hands, issuing it under the new title of Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, but continuing the numbering sequence, and later reissuing the earlier numbers with the new name.

In editing the second incarnation of his magazine, Blackwood was heavily dependent on the assistance of two young lawyers-turned-writers, John Wilson (1785–1854) and John Gibson Lockhart (1794–1854). The editorial identity remained veiled in uncertainty and obfuscation, and with good cause, since from the very first number under the new editorial arrangement, the magazine not only caused offence, but opened itself to legal action. The most notorious contribution, the infamous 'Translation from an Ancient Chaldee Manuscript', parodied, in mock-biblical form, Edinburgh's literary elite. Written by Wilson, Lockhart, and the poet James Hogg (1770–1835), it caused such a furore that it was removed from later editions of the magazine. Other contributions, however, were almost equally shocking—notably Lockhart's attacks on Coleridge and on Leigh Hunt and 'the Cockney School of Poetry'—and Blackwood's ambition to break the mould of monthly journalism was to this extent immediately fulfilled. The first issue made a sensational impact, and the continuing contributions of the lively wits of Blackwood's circle ensured the magazine a significant reputation and readership, and served to establish a new, much more personal form of magazine journalism, which rapidly supplanted the mores of the established miscellanies. Despite the magazine's radical new departure, however, there was more continuity with the past than might at first appear. Certainly, both the content and form of the magazine had changed. Cleghorn and Pringle had subdivided the magazine into the traditional sections: 'Original Communications', 'Select Extracts', 'Antiquarian Repertory', 'Original Poetry', 'Review of New Publications', 'Periodical Works'/'Analytical Notices', 'Literary and Scientific Intelligence', 'Works Preparing for Publication', 'Monthly List of New Publications', and 'Monthly Register' (this was subdivided into home, foreign, and political news reports, commercial, agricultural, and meteorological reports, and births, marriages, and deaths). Now, however, the main body of the magazine was reorganized so that articles of many kinds, both humorous and serious, poetry and prose, appeared cheek by jowl in an undivided section. In the number for March 1818, two stanzas which appeared in the unpaginated 'Notices to Correspondents' characterized the change: 'A Berkshire Rector has been pleased to wonder / Why we've dismissed the primitive arrangement. / He hates, he says, from verse to prose to blunder. / Begging our good friend's pardon, We prefer / To mix the dulce with the utile, / And think it has in fact a charming air / Such different things in the same page to see'. Yet, while this was a striking change, the magazine retained the structure of its concluding sections—the 'Literary and Scientific Intelligence' and 'Monthly Register'—only shedding the former after February 1821 (Flynn [2007?]). The continuance of the traditional 'Literary and Scientific Intelligence' and of serious scientific articles in the early volumes of the magazine is an important feature which went largely unregarded by scholars until Philip Flynn's recent studies. As Flynn points out (2006, p. 146), 'much of what was ùtile' about the early Blackwood's 'were articles on different aspects of contemporary biological and physical sciences'. In the first volume of the reformed journal, he observes, 'there were 15 articles, essays, or notices on contemporary imaginative literature and its creators, and 29 articles, essays, or notices of scientific interest'. Much of this was provided by such distinguished men of science as David Brewster and Robert Jameson, and by John Wilson's naturalist brother James. Yet from a high point of fifty-one scientific articles in the first year, Flynn traces a preciptitous decline in successive years, through thirty-one in 1818–19 and sixteen in 1819–20 to five in 1820–21 (Flynn [2007?]). In part, no doubt, this was prompted by the founding of Constable's specialist scientific monthly, the Edinburgh Philosophical Journal, in 1819. The new journal appeared intially under the joint editorship of Jameson and Brewster, but the latter subsequently left to found the Edinburgh Journal of Science in 1824 with Blackwood. However, the decline in the number of dedicated scientific articles in Blackwood's was matched by a similar decline in other classes of serious non-fiction articles, most notably those relating to antiquarianism and Scottish life. Shuffling off the trappings of the eighteenth-century repository of learning and becoming more literary and political, the magazine thus gradually took shape in the more recognizable form which the other magazine editors emulated from the 1820s. In this way, Blackwood's provides a powerful illustration of the co-creation at this period of specialized scientific and literary magazines from the earlier, avowedly universal form of magazine (see Dawson, Noakes and Topham 2004). | |

Notes on Indexing | |

The indexing offered here of Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine provides a snapshot of the journal's early content, allowing the reader to contrast the first two volumes, with their very different editorial styles. The set of the magazine used is not the first printing either of the first volume, or of the first issue of the second. In the former case, this makes no tangible difference, since the name change is the only recorded alteration. In the latter, the second edition of issue 7 contains 'Strictures on an Article in No. LVI of the Edinburgh Review' in place of the withdrawn 'Chaldee Manuscript', as well as modifications to the article on the 'Cockney School' (see Mason 2006). Where possible, anonymous authors have been identified using Strout 1959. | |

Bibliography | |

Dawson, Gowan, Noakes, Richard, and Topham, Jonathan R. 2004. 'Reading The Magazine Of Nature', in Reading the Magazine of Nature: Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical, by Geoffrey Cantor et al., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–34. Finkelstein, David 2002. The House of Blackwood: Author-Publisher Relations in the Victorian Era, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. Finkelstein, David, ed. 2006. Print Culture and the Blackwood Tradition, 1805–1930, Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Flynn, Philip 2006. 'Beginning Blackwood's: The Right Mix of Dulce and Ùtile', Victorian Periodicals Review, 89, 136–57. Flynn, Philip [2007?]. 'Beginning Blackwood's: The First Hundred Numbers (April 1817–May 1825)', <http://www.english.udel.edu/Profiles/flynn_blackwood.htm>, accessed November 2007. Mason, Nicholas, ed. 2006. Blackwood's Magazine, 1817–25: Selections from Maga's Infancy, 6 vols, London: Pickering & Chatto. Strout, Alan Lang 1959. A Bibliography of Articles in 'Blackwood's Magazine', Volumes I through XVIII, 1817–1822, Lubbock, TX: Library, Texas Technological College. Wallins, Roger P. 1986. 'Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine', in British Literary Magazines: The Romantic Age, 1789–1836, ed. by Alvin Sullivan, Westport CT and London: Greenwood Press, 45–53. | |

Jonathan R. Topham (Nos. 1 and 7) and Fern Elsdon-Baker (No. 2–6, 8–12) | |