|

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, 1822–47 | |

Sequence |

Volumes 1–12, 1822–28 |

Editor |

Thomas Byerley, 1822–26 |

Publisher |

John Limbird, 1822–41 |

Printer |

John Limbird, 1822–41 |

Price |

2d. (1822–46) |

Format |

Demy 8vo. |

Pages |

16 (1822–46) |

Frequency |

Weekly (1822–46) |

Circulation |

10,000 (1823),15,000 (1837) |

Indexes |

All volumes |

Digital |

Full transcriptions of the Mirror of Literature, vols 10,

12–14, 17, 19–20 (July–December 1827, July

1828–December 1829, January–June 1831, January–December 1832)

are freely available via

The

Online Books Page. |

Copies |

Sheffield University Library (vols. 1–2, 4–12) |

Introduction | |

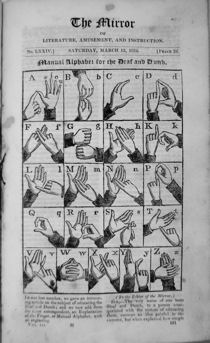

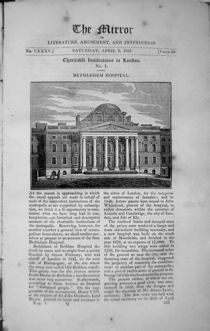

While the Mirror was not the first cheap miscellany to be published in Britain, it was the first to achieve significant and lasting success, becoming an emblem of and inspiration for the first wave of cheap journalism in the 1820s. It was projected by John Limbird (1796?–1883), a small-time bookseller and stationer in the Strand, whose involvement with the radical press meant that he had witnessed at close quarters the staggering success enjoyed by the unprecedentedly cheap twopenny edition of William Cobbett's Weekly Political Register, issued from November 1816. Cobbett's 'two-penny trash' reportedly sold up to 70,000 copies per week, and, following the government's suppression of such radical political journals in 1819, Limbird was one of a number of publishers and editors who sought to capitalize on the format to produce a cheap apolitical miscellany aimed at a similarly large readership. Limbird's first involvement in journal publication had been with two publications aimed at undercutting the innovative weekly Literary Gazette (1817–63), namely the Literary Journal (1818–19) and its more auspicious successor the Literary Chronicle (1819–28). At sixpence, however, neither was cheap enough to justify the grandiose rhetoric of being a 'PAPER FOR ALL'. Limbird's first twopenny periodical—an essay-journal entitled the Londoner (1820) and apparently modelled on Leigh Hunt's Indicator (1819–21)—was aimed at an altogether larger market, but it failed after five issues. It was not until after the commencement in August 1822 of the twopenny Hive; or, Weekly Entertaining Register (1822–24), that Limbird pinpointed a successful format for a twopenny weekly. When Limbird began the Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction in November 1822, it emulated the Hive in presenting an assemblage of short contributed articles and copious extracts from old and new publications, spread over sixteen octavo pages in double columns. Its main innovation, however, was to include at first one, and then frequently two wood engravings per number, which constituted a major attraction.  The Mirror was an almost instant success and within months it had drawn dozens of competitors into the field, though few of these survived long. By 1825, Henry Brougham was able to cite the miscellany as one of the foremost indications of the educational good that could be achieved by cheap publishing, claiming that 'of some issues, upwards of 80,000 copies have been sold' (Brougham 1825, p. 3). Although the first number ultimately sold over 150,000 copies, a circulation of 10–15,000 copies was probably more typical (Topham 2005a, p. 76). Nevertheless, the journal's claim to have 'created a new era in the history of periodical literature' (vol. 5 (1825), p. [iii]) was not unreasonable. The success of the Mirror owed more than a little to its accomplished editor, Thomas Byerley (1788–1826). The son of a Yorkshire cartwright, Byerley had received a grammar school education before coming to London, where he worked on Richard Phillips's Monthly Magazine, and ultimately became editor of Limbird's Literary Chronicle and the Star newspaper. He was an exceptionally able wielder of scissors and paste, and between 1820 and 1823 he produced with Joseph Clinton Robertson The Percy Anecdotes, a twenty-volume part-work consisting of a catalogue of anecdotes culled from a range of sources, which was crowned with considerable success. He was thus a natural choice for Limbird, the success of whose journal depended not a little on its making available attractively selected extracts from contemporary books and periodicals whose price made them otherwise inaccessible to his readers. Byerley also ensured the moral and political circumspection which was a key aspect of the journal's wide appeal. For, despite his early flirtation with radical publishing, Limbird realized that an apolitical stance was critical, both in maximizing his readership and in avoiding any of the difficulties experienced by the radical press suppressed in 1819. Limbird's role in making the Mirror a success extended to finding innovative means of distribution. It is reported that large parts of the retail trade refused to sell the journal, denigrating it as 'trash', and that the London wholesale houses refused to include the weekly parcels in their dispatches to the provincial trade (Anon 1859, p. 1326). As a result, Limbird was obliged to travel around the new industrial towns of the Midlands and North, establishing agencies with shopkeepers whether they were booksellers or not, and employing men to post placards on walls and distribute handbills. In this way, both the Mirror and the twopenny part publications of standard works which Limbird soon began to issue, circumvented the standard trade network. This innovation did not, however, go unopposed. Limbird received representations from Paternoster Row about undermining the reprint trade, and more than once his publishing of extracts in the Mirror and elsewhere was subjected to legal challenges.  Congruent with its price, and with the intention of maximizing its circulation, the Mirror's contents were pitched at a mass audience. Byerley claimed that the rapid growth in elementary literacy had made it necessary 'to give the public at large a journal which, while it embraced the most ample range over the vast domain of English literature, should be published at a price that would place it within the reach of ALL' (vol. 3 (1824), p. [iii]). As we have seen, this inclusive rhetoric had been a common feature of Limbird's earlier, more expensive journals, but while the Mirror was claimed to circulate among all classes of society, it is clear that a significant proportion of sales were among the wealthier classes. Certainly, the articles contributed by readers were generally written in the manner of learned gentlemen, and often drew on significant library resources. Moreover, the only one of Byerley's contributors identified to date, Peter Thomas Westcott ('PTW'), was a 'gentleman of independent property' (Timbs 1871, p. 614). Nevertheless, the extent of its maximum circulation clearly implies that at least some of the issues were bought by lower middle-class and working-class readers. The Mirror underwent a number of significant changes over its quarter century of existence. The most important alteration that took place during the run indexed here was the change of editor following the untimely death of Thomas Byerley in July 1826. Byerley was reportedly followed in the editorial chair by an unidentified 'Mr Ray', whose editorship lasted only around six months (Anon 1859, p. 1326). Beginning with the issue of 29 September 1827, however, the journal was continued by a well-established hack writer, John Timbs (1801–75), who, like Byerley, had begun as a contributor to the Monthly Magazine, becoming amenuensis to its publisher, Richard Phillips, in 1821 (Timbs 1871, pp. 396 and 614). Timbs conducted the journal along broadly the same lines as Byerley, steering it through the advent of the new penny weeklies of the 1830s, and apparently maintaining its circulation. Ultimately, however, the journal passed out of John Limbird's control, and under several publishers in the 1840s it seems to have struggled to maintain its readership, with the ever-increasing range of cheap weekly and monthly periodicals. Several new series were commenced, and with one of these in the summer of 1846 the Mirror became a literary monthly, eschewing all extracts and promising only original material. At the start of 1850, after a spell as the Mirror Monthly Magazine, the journal was again reinvented, this time as the London Review, but only lasted six issues before its final demise (Dodson 1986). | |

Notes on Indexing | |

The Mirror combined elements of weekly synoptic journalism with elements more typical of the eighteenth-century monthly miscellany. The initial advertisement for the journal had promised to provide 'The Spirit of the most expensive Works' and 'The Spirit of the Public Journals', and extracts from and abstracts of new and recent publications formed a significant attraction (Topham 2004b, p. 45). In addition, however, the magazine was dependent on original contributions and extracts sent by readers or penned by the editor, rather in the style of the Monthly Magazine on which Byerley had cut his literary teeth. While these several components did not appear within a rigid and tightly ordered structure, the individual issues manifested a broadly consistent organization. Generally, they began with a number of editorial and contributed articles, the first one usually being illustrated. In the central portion of each issue there appeared two core sections: extracts from contemporary magazines appeared under the heading 'Spirit of the Public Journals' and from the third volume this was supplemented by 'The Selector; or, Choice Extracts from New Works'. Another regular section was 'The Gatherer', comprising anecdotes and epigrams, which usually appeared near the end of the issue. Over time, however, new sections and numbered recurrent features appeared (e.g. 'The Novelist', 'Scientific Amusements', and 'The Sketch Book'), and since these did not appear in every issue the journal had a somewhat irregular appeareance. From its inception, the Mirror carried a significant amount of scientific material, distributed widely across its miscellaneous components. However, the generic diversity and structural multiformity of the journal meant that these different kinds of scientific references often appeared in close proximity to each other and to other material, providing a fascinating melange. One important context for discussion of scientific subjects was in the editorial and contributed articles, which, as we saw above, often took the form of the learned contributions to older, gentlemanly miscellanies. Such articles were very various, ranging from brief paragraphs and sets of instructions to histories, biographies, and essays, but they were typically based on the resources of a scholarly library, sometimes including extensive references. In addition, however, the sciences frequently featured in the extracts from contemporary journals and other fashionable literature. Since a wide range of publications was plundered for extracts, the references to science were similarly diverse. One particularly significant source of extracts was the new literary monthlies of the 1810s and 1820s—Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, the New Monthly Magazine, and the London Magazine—which often provided potent representations of the sciences within fiction and poetry (Topham 2004b, pp. 51–52). A particularly interesting development in the inclusion of scientific material in the Mirror dates from the death of Byerley, and the transition to the editorship of Timbs. While, under Timbs, the magazine continued to include contributions from readers, a significantly smaller proportion of the articles on the sciences came from this source. In October 1827 Timbs began a new section, entitled 'Arcana of Science; or, Remarkable Facts and Discoveries in Natural History, Meteorology, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Geology, Botany, Zoology, Practical Mechanics, Statistics, and the Useful Arts', which promised to provide 'all new and remarkable facts in the several branches of science', selected 'from the Philosophical Journals of the day, the Transactions of Public Societies, and the various Continental Journals' (vol. 10, p. 252). Drawing on the new specialist scientific periodicals of the 1820s, Timbs thus represented himself as making 'popular science' available to his readers (vol. 12, p. iv), where previously it had been chiefly from learned contributors that dedicated scientific articles had been derived. The indexing provided here covers the period from the journal's inception, and through the period of transition to Timbs's editorship. With an average of almost six indexed articles per weekly issue, the Mirror presents the indexer with a daunting task. Priority has been placed, therefore, on identifying the subjects, references, and (where appropriate) the sources of articles. Fewer than a third of index entries have descriptions, and these are usually introduced to help readers locate and contextualize the material of interest in articles that are not explicitly scientific. | |

Bibliography | |

Anon 1859. 'The Pioneer of Cheap Literature', Bookseller, 30 November 1859, pp. 1326–27. Brougham, Henry Peter 1825. Practical Observations Upon the Education of the People: Addressed to the Working Classes and their Employers, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green [...] for the benefit of the London Mechanics Institution. Dodson, Charles Brooks. 1986. 'The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction', in British Literary Magazines: The Romantic Age, 1789–1836, ed. by Alvin Sullivan, Westport CT and London: Greenwood Press, 308–12. Timbs, John 1871. 'My Autobiography: Incidental Notes and Personal Recollections', Leisure Hour (1871), 20–23, 85–88, 181–84, 212–15, 266–69, 293–95, 347–51, 394–98, 420–24, 469–72, 500–03, 596–600, 612–15, 644–48, 685–88, 692–96, 730–33, and 794–99. Topham, Jonathan 2004. 'The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction and Cheap Miscellanies in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain', in Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical: Reading the Magazine of Nature, by Geoffrey Cantor, et al., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 37–66. Topham, Jonathan 2005. 'John Limbird, Thomas Byerley, and the Production of Cheap Periodicals in the 1820s', Book History, 8, 75–106. | |

Jonathan R. Topham | |